Cuba, Chernobyl and COVID-19

Posted: 13th July 2020

Posted on July 12, 2020 by beyondnuclearinternational

Cuba’s doctors have been to the rescue before — to save Chernobyl’s children

By Linda Pentz Gunter

“We do not give what we have in excess; we share all that we have,” said Dr. Julio Medina, director of a Cuban medical program outside Havana that treated children from Chernobyl, in a May 2009 article in The Guardian. “It is simple.”

Today, as Cuban doctors travel the world treating the patients of COVD-19, it is still simple. It is, as the Chernobyl program was before it, “a commitment of solidarity.”

Yet Cuba is not without cases of the viral pandemic at home. In fact, the UK-based Cuba Solidarity Campaign (CSC) recently set up a fundraiser to “provide urgent medical aid to help Cuba during the coronavirus pandemic,” and specifically to purchase “ventilators, testing kits and personal protective equipment to support Cuban health workers in the fight against COVID-19 on the island.”

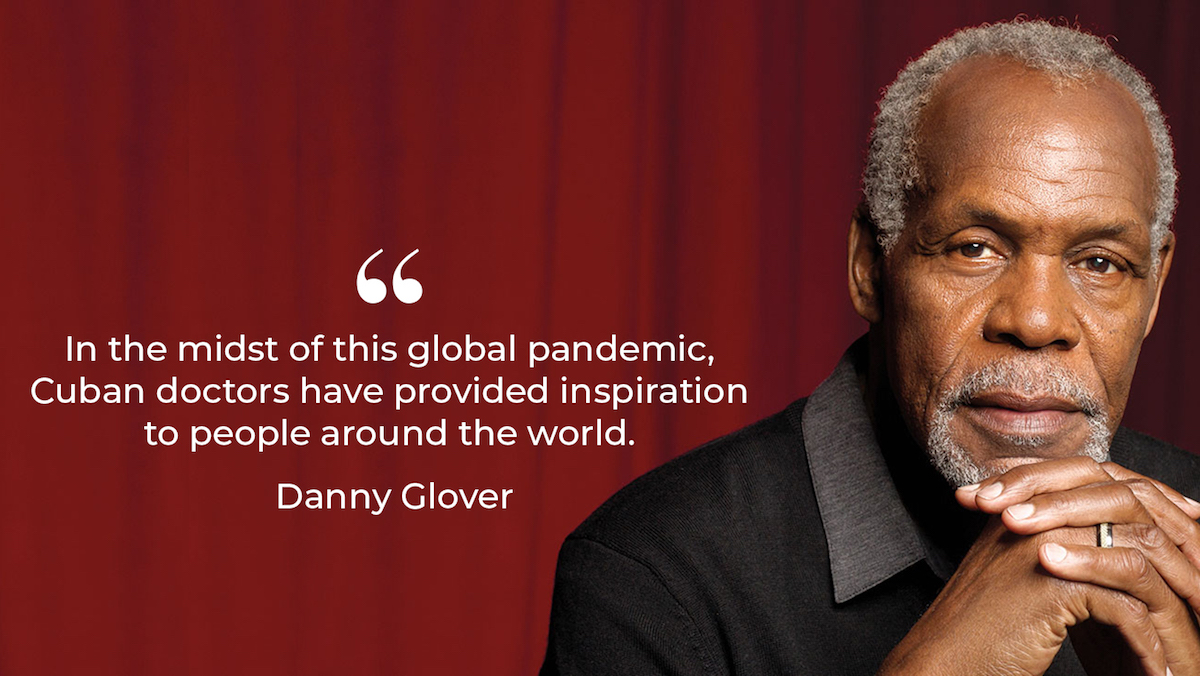

The CSC, Code Pink, actor Danny Glover and others are calling on the Nobel Committee, via a petition, to award the Cuban doctors — known as the Henry Reeve Brigade — the Nobel Peace Prize, not only for their efforts today, but for their previous rescue missions when ebola struck in West Africa, and cholera in Haiti.

The story of Cuba’s involvement in helping the children of Chernobyl, however, is less well known if at all. It was a free program that lasted an astonishing 21 years, beginning in 1990. In 2019 it resumed, this time to help “the sons and daughters of the victims, who are showing ailments similar to those of their parents,” according to Miguel Faure Polloni, writing in Resumen.

How Cuba helped treat Chernobyl’s children is a little known story brought to light in Un Traductor

The Chernobyl children’s improbable journey was most vividly told in an award-winning 2018 feature film from Cuba — Un Traductor (A Translator) — which brought us the dramatized true story of a Cuban professor of Russia who finds himself ordered to report to a hospital instead of his classroom, there to serve as a translator for “the patients from Chernobyl” and their families.

Beyond Nuclear is honored to partner with the Goethe-Institut DC and the Heinrich Böll Stiftung, Washington, DC to present Cuba, Chernobyl and COVID-19: a live online event on Tuesday, July 21, at 5pm Eastern Time. The event features the directors of Un Traductor — Sebastián and Rodrigo Barriuso —discussing their film and the moving true story behind it that eventually resulted in more than 25,000 children from Chernobyl being treated in Cuba. They will be joined by historian and author, Kate Brown, and the Goethe-Institut representative in Cuba, Michael Thoss.

Please join our live event by replying to this Eventbrite invitation, after which you will receive a zoom link to register for the event. If you live in the US or Canada, you will be sent a private Vimeo link to view Un Traductor for free. If you live outside the US and Canada, you can rent the film on iTunes for $1.99.

Why were the Chernobyl children in Cuba? And why did they continue to come for more than two decades, to be followed now by their own children? Kate Brown, author of Manual for Survival. A Chernobyl Guide to the Future, is best positioned to answer that question, having conducted extensive research on the topic. Her book explodes the myth that only 54 liquidators died as a result of the 1896 nuclear disaster in Ukraine, then part of the Soviet Union.

As the film shows, children continued to come to Cuba, largely from Ukraine, even as the island itself began to feel the grip of austerity. As the Berlin Wall and then the Soviet Union crumbled, an economic crisis hit Cuba, including food and petrol shortages. But, as Dr. Medina told Telesur in 2017: “Though Cuba endured difficult economic times during the Special Period, our country continued providing specialized healthcare for those children.”

The early victims mainly suffered from thyroid cancer and leukemia, but over the years doctors and nurses in Cuba most commonly treated thyroid hyperplasia, vitiligo and alopecia. The children also suffered considerable psychological trauma related to their conditions. At Tarará, the hospital just outside Havana that became the center for treatment of Chernobyl victims, the children were also educated and allowed time to enjoy the beach at what was once an aristocratic resort under the Battista regime that the Cuban Revolution overthrew.

Today, as Cuba manages the novel coronavirus pandemic at home while treating thousands of patients abroad, several Republican Senators, with the support of the White House, are leading an attempt to sabotage those efforts. As Code Pink writes, “the Trump administration has been demonizing Cuba’s doctor program and intensifying its blockade against Cuba, going so far as to block a shipment of much-needed coronavirus medical supplies.”

The “demonizing” includes characterizing the overseas efforts of Cuban medical personnel as tantamount to “human trafficking,” with the US warning other countries not to use their services.

The US economic and financial blockade against Cuba has lasted almost 60 years. Now, there are numerous calls for it to end, including from UN Special Rapporteurs, who said in an April statement that “In the pandemic emergency, the lack of will of the US Government to suspend sanctions may lead to a higher risk of such suffering in Cuba and other countries targeted by its sanctions”.

Michael Thoss, cultural mediator and representative of the Goethe-Institut in Havana, pointed out that while Cuba’s medical services are free to its populace, medicines are in short supply as a result of the US blockade.

And in an article for Der Tagsspiegel Thoss noted the irony: “While the US is exerting increased pressure on pharmaceutical companies in the corona crisis not to supply the Cuban population with medication and respiratory equipment, Cuba’s medical delegations are sending out a signal of international solidarity.”

And as Dr. Doreen Weppler-Grogan of the CSC wrote in a June 2019 letter to The Guardian, Cuba responded to the Chernobyl medical crisis as “an ethical and moral” question. “No other country in the world,” she pointed out, “launched such a massive programme.”

Headline photo courtesy of Code Pink.