Nuclear Gulf: Experts sound the alarm over UAE nuclear reactors

Posted: 15th July 2020

From environmental disaster to a nuclear arms race, experts warn of layers of risks surrounding Barakah nuclear plant.

MORE ON NUCLEAR ENERGY

If there is one lesson the world can learn from the coronavirus pandemic, it is that theoretical, border-breaching catastrophes can suddenly become very real and very deadly.

Nuclear energy experts have long understood this. They spend their entire careers thinking about and trying to mitigate low-probability, high-impact risks.

After all, nuclear power plants have been around since the 1950s. The roughly 440 nuclear power reactors currently in use today mostly hum along unnoticed – splitting atoms to release energy, generating heat that powers steam turbines to produce electricity.

Put simply, nuclear power reactors boil water – an overwhelmingly uneventful process.

Until the unthinkable happens.

Chernobyl. Fukushima. Both infamous accidents. Both rooted in human error. And to date, the only ones rated as seven – the highest level of severity on a scale created by the United Nations’ nuclear watchdog, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Nearly a decade on from Fukushima and three and a half decades after Chernobyl, nuclear power no longer dominates global discussions – in part because many countries are moving away from it, decommissioning reactors, or scrapping or scaling back nuclear energy projects in favour of far cheaper, much safer renewable energy solutions like wind and solar.

But as much of the world looks for ways to move on from 20th-century fission energy and embrace sustainable, more fiscally responsible 21st-century options, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) is going nuclear.

This is the wrong reactor, in the wrong place, at the wrong time.PAUL DORFMAN, FOUNDER AND CHAIR OF THE NUCLEAR CONSULTING GROUP

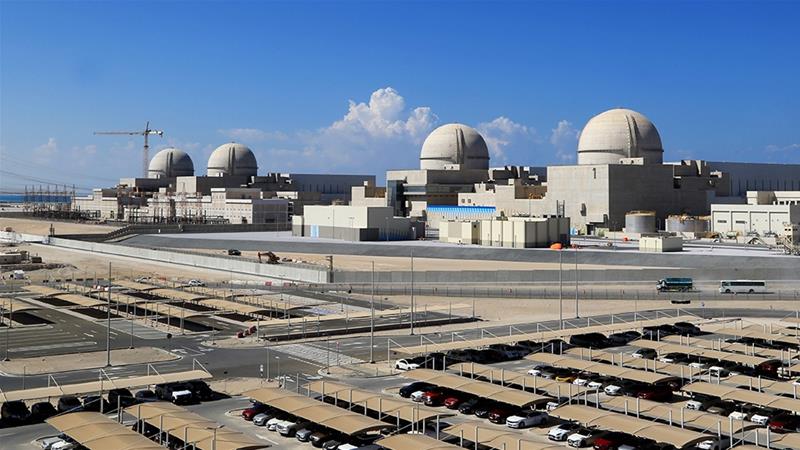

In March, the UAE finished loading fuel rods into one of four brand-new nuclear reactors at the Barakah nuclear power station – the first on the Arabian Peninsula.

Years behind schedule and billions of dollars over budget, Barakah – Arabic for “divine blessing” – has been hampered by construction problems that were not disclosed in a timely fashion, and a paucity of properly trained staff to run the plant.

The UAE is adamant its intentions are peaceful. It has agreed not to enrich its own uranium or reprocess spent fuel, and has signed up to the IAEA’s Additional Protocol, significantly enhancing the agency’s inspection capabilities.

It has also secured a coveted 123 Agreement with the United States – a seal of approval from Washington that paves the way for bilateral civilian nuclear cooperation including the transfer of nuclear material, equipment and components.

Still, nuclear energy specialists are sounding the alarm over the potential fallout the UAE reactors could visit upon the Gulf, an ecologically fragile and geopolitically volatile patch of planet Earth.

What they describe is not one potential risk, but layers of them – from an environmental disaster, to theft of radioactive materials, to a nuclear arms race between regional rivals.

Among the concerned is Paul Dorfman, Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the Energy Institute, University College London and founder and chair of the Nuclear Consulting Group.

Dorfman advises governments on nuclear radiation risks. And governments take his advice.

His verdict on Barakah: “This is the wrong reactor, in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Vulnerable to attack

Nuclear weapons are designed to kill. Nuclear power plants are designed to produce power for society at large. But talk to a nuclear specialist, and the line separating a military weapon from a civilian-use reactor can quickly blur.

“There’s an old saying, which is a nuclear power plant in a country is like a pre-deployed nuclear weapon for the enemy,” Mycle Schneider, convening lead author and the publisher of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report (WNISR), told Al Jazeera. “People don’t realise, but the radioactive inventory in a nuclear power plant is much, much larger than what is in a nuclear weapon.”

The accident at Chernobyl, for instance, released 400 times more radioactive material into the planet’s atmosphere than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima by the US, according to the IAEA.

But a radioactive release does not have to stem from human error. It could also result from a deliberate attack on a nuclear reactor. And the Middle East has witnessed more of those than any other region on Earth.

“This is not a place that allows for mere academic speculation about the possibility of someone else taking a whack at a reactor,” Henry Sokolski, executive director of the Nonproliferation Policy Education Center, told Al Jazeera. “If you go back just even a few years, you can get to 13 aerial strikes against reactors in the region.”

Those reactors were located in Iraq, Iran and Israel, and include a suspected one under construction in Syria that Israel bombed.

Iraq’s reactors were destroyed. Israel has two reactors in operation and Iran operates a nuclear power plant at Bushehr.

Now, the UAE is adding the Arab world’s first nuclear power plant into that Middle East mix.

If you go back just even a few years, you can get to 13 aerial strikes against reactors in the region.HENRY SOKOLSKI, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR OF THE NONPROLIFERATION POLICY EDUCATION CENTER

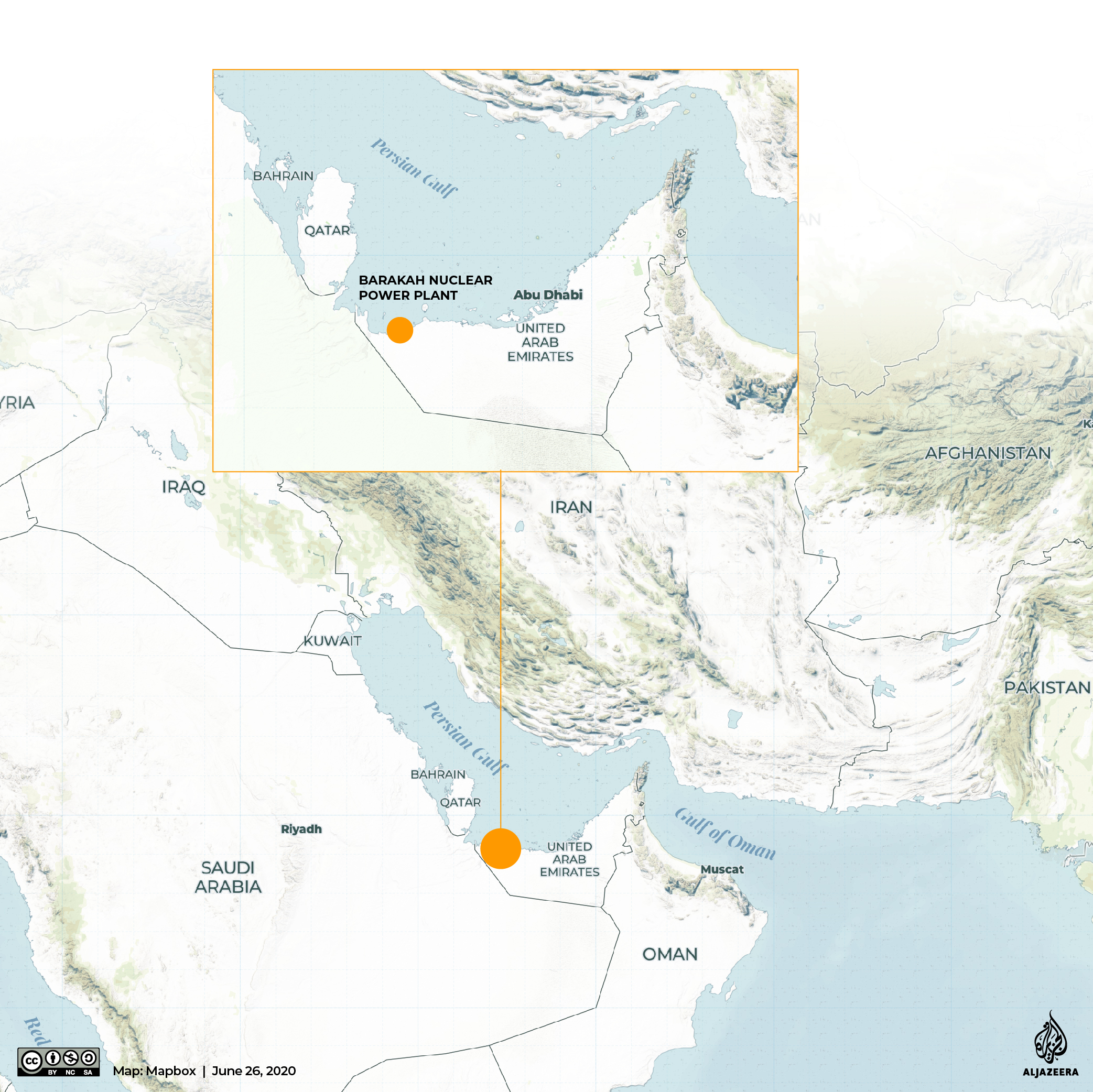

Located in the Dhafra region of Abu Dhabi, the Barakah nuclear power plant has four reactors, the first of which is fully constructed and had fuel rods loaded in March this year.

Emirates Nuclear Energy Corp (ENEC), which is building and operating the plant, says it will provide 25 percent of the UAE’s electricity needs when all four reactors are fired up and plugged into the grid.

This spring, ENEC’s CEO said the first reactor would reach “criticality” – the point of a sustained chain-reaction (nuclear fission) – “very soon”.

It has been a long time coming. Barakah is three years behind schedule and has been plagued by problems stemming from what experts describe as a cut-rate design and poor construction that would not fly in safety-conscious Europe.

The Barakah reactors are the first and only export order secured by South Korea’s Korea Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO), which won the UAE contract with a bid that was reportedly about 30 percent lower than the next-cheapest one.

“It’s concerning that in a volatile area, these reactors are being built in what seems to be a relatively cheap and cheerful kind of way,” said Dorfman. “The Barakah reactor, although it is a relatively modern reactor, it does not have what is known as ‘Generation III+ [three plus] Defense-in-Depth’. In other words, it doesn’t have added-on protection from an airplane crash or missile attack.”

Those missing defence features include what Dorfman describes as “a load of concrete with a load of reinforced steel” for extra protection from an aerial attack and a “core catcher” that literally catches the reactor core if it melts down.

“Both of these engineering groups would normally be expected in any new nuclear reactor in Europe,” he said.

And Europe is not nearly as volatile as the Gulf, where as recently as September, Saudi Arabia’s oil facilities at Abqaiq and Khurais were attacked by 18 drones and seven cruise missiles – an assault that temporarily knocked out more than half of the kingdom’s oil production.

“I would say that they [Barakah reactors] are as vulnerable as Saudi Arabia’s Abqaiq facility was, which was protected by three layers of missile defence,” said Sokolski.

Aerial assaults are just one potential avenue of attack. The UAE has pledged not to enrich its own uranium, so it has to import it. The UAE plans to cool spent fuel rods on site in pools, but according to ENEC’s website, it has no long-term storage policy in place yet.

“What you’ll see is nuclear fuel rods and fuel coming in and high-level waste going out,” said Dorfman. “Now accidents and incidents on this high-level stuff could prove deeply problematic. And we know even into the Arabian Sea there’s questions about piracy.”

Ripe for human error

Beyond the spectre of a deliberate attack or theft of radioactive materials, experts also worry that Barakah could witness an accident caused by human error.

Every country needs a nuclear regulatory body to ensure the safe operations of reactors. In the UAE, that job falls to the Federal Authority for Nuclear Regulation (FANR).

Established in 2009, FANR boasts on its website that it has “achieved remarkable success in the UAE’s peaceful nuclear programme through transparency in its operations”.

But Barakah has a troubling record of less-than-timely disclosures of problems.

Cracks in Barakah’s number-three containment building were detected in 2017, but the Director General of FANR, Christer Viktorsson, only publicly disclosed this in November 2018, during an interview with the publication Energy Intelligence.

In most cases, there’s more information available on the progress of construction than is the case in the UAE.MYCLE SCHNEIDER, CONVENING LEAD AUTHOR AND THE PUBLISHER OF THE WORLD NUCLEAR INDUSTRY STATUS REPORT

Cracks are a serious issue because containment buildings are supposed to prevent a radiological release into the atmosphere should an accident happen.

ENEC did not release a statement about the cracks in the number-three unit until December 2018, when it further admitted that cracks had also been found in Barakah’s number-two containment building.

“ENEC’s reluctance to reveal any details speaks volumes about the transparency of the Barakah new build,” said Dorfman.

Cracks were eventually detected in all four Barakah containment buildings.

“I can definitely say that in most cases, there’s more information available on the progress of construction than is the case in the UAE,” said Schneider. “It seems to be particularly problematic to access information in this country [the UAE], which is somewhat worrying when it comes to high-risk technologies.”

When proper oversight is lacking at nuclear facilities, the impact on people and the planet can be devastating.

The independent investigation committee appointed by Japan’s national legislature to look into the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant concluded that it was not the result of the earthquake and tsunami that shook Japan on March 11, 2011, but “a profoundly manmade disaster – that could and should have been foreseen and prevented”.

But it is not only nuclear regulators who can drop the ball. Nuclear workers need to be properly trained in their jobs and steeped in a culture that promotes public safety above all other considerations.

Here too, experts find Barakah wanting.

FANR did not issue an operating licence to Barakah in 2017 – the year it was originally scheduled to go online. At the time, ENEC said the start-up date had been pushed back to allow more time to ensure safety standards and reinforce “operational proficiency” for plant workers.

“There are some real concerns about the training levels [of nuclear workers],” said Schneider, adding that while he thinks there “are very serious doubts about the independence” of FANR, even the UAE’s nuclear regulator was “not convinced that the level of training was sufficient to start up the first [Barakah] reactor.”

Neither ENEC nor FANR responded to Al Jazeera’s requests for an interview to discuss the concerns surrounding Barakah.

What spills in the Gulf hangs around in the Gulf

Attack or human snafu, the question then becomes, what happens to the UAE and its neighbours if radiation from Barakah is released into the surrounding environment?

There are so many variables to consider, the disaster scenarios are boundless. But past nuclear incidents can offer a window into the public health problems that can arise, from elevated levels of certain kinds of cancers, DNA damage and death, to social disruptions, community breakdowns and anguishing social stigmas suffered by survivors.

One variable attached to Barakah that troubles nuclear specialists and other scientists is the unique ecosystem of the Gulf.

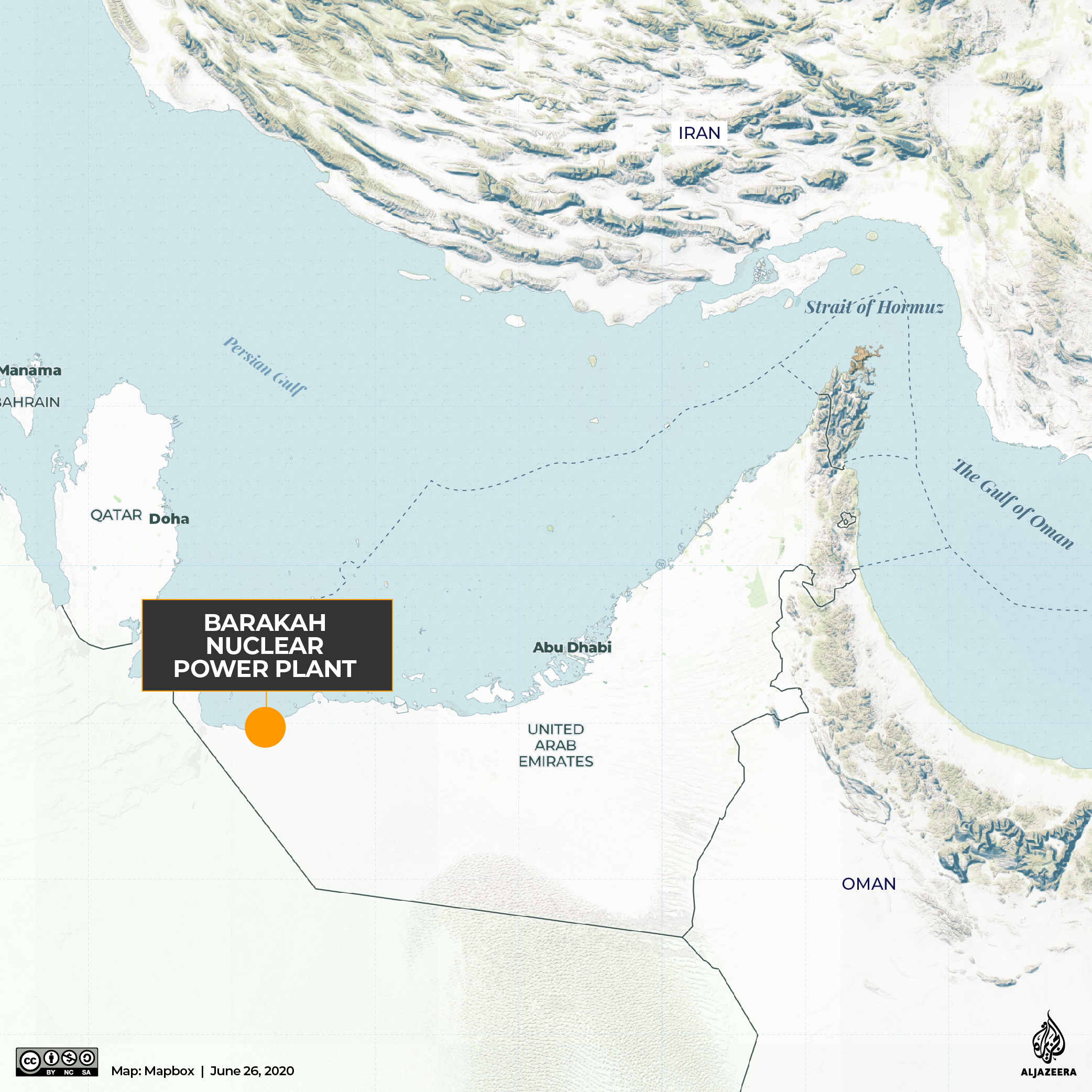

Most of the radiation released during the Fukushima accident ended up in the Pacific Ocean – which is vast, cold and deep – enabling it to disperse over a wide area. The Gulf, by comparison, is far smaller, warmer and shallower.

Roughly 600 miles (965km) long, the Gulf’s width varies from just over 200 miles (322km), narrowing to around 35 miles (56km) at the Strait of Hormuz, where during the spring, the tidal range is only 1.2 metres.

“It’s a very stressed water body in terms of the ecosystem,” said Roger A Falconer, emeritus professor of Water Engineering at Cardiff University.

Falconer has studied three-dimensional computer models of the Gulf, mapping so-called “residence times” – the average time a parcel of water or a spillage, like oil, hangs around in the Gulf before it is flushed out via the Strait of Hormuz.

“To get from Abu Dhabi to the Strait of Hormuz, it would typically take two years, which is a long time,” Falconer told Al Jazeera.

“I would have thought it was better to put the nuclear power station on the other side of the Strait of Hormuz outside the basin,” he added.

The prospect of radioactive material polluting the Gulf is even more worrisome, say experts, when you consider that it has the highest concentration of water desalination plants on Earth, and no liability regime in place to determine who pays for what if a radiation incident happens.

“It would be enormously helpful if the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] states got together and started thinking about a liability regime, a liability structure to think through what if something happens,” said Dorfman.

The financial toll of a nuclear accident can be staggering. Japan’s government estimated in 2016 that the final price tag for cleaning up Fukushima will be north of $200bn, while the Japan Center for Economic Research reckons it could cost more than three times that amount. And most of the radioactive contamination from Fukushima blew out to sea – not toward heavily populated areas like Tokyo.

The market just says ‘no’ to nuclear

When the UAE launched its nuclear programme back in 2009, nuclear energy was sold as a “significant contribution” to the country’s economy as well as its future energy security.

The initial projected cost for the plant was $20bn. But thanks to delays, that figure had ballooned to more than $24bn by 2016. Some estimates put the total cost of the Barakah build at around $28bn to $30bn.

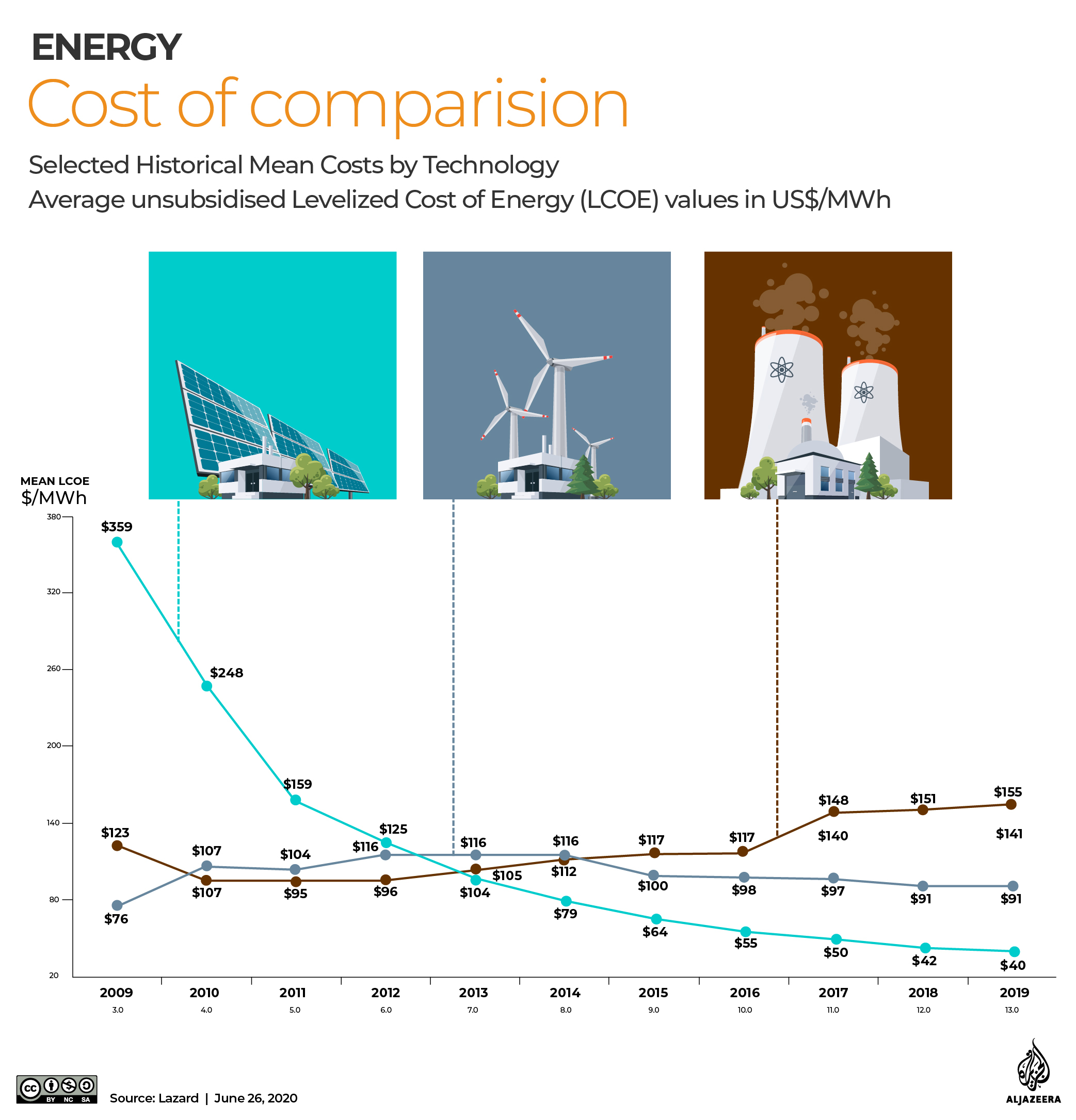

While the bill for Barakah was climbing, the price of greener, renewable energy started plummeting dramatically.

Between 2009 and 2019, utility-scale average solar photovoltaic costs fell 89 percent and wind fell 43 percent, while nuclear skyrocketed 26 percent, according to an analysis by the financial advisory and asset manager Lazard.

Zoom in on the Gulf, and the market case for nuclear really starts to break down.

According to the forthcoming 2020 edition of the WNISR, the latest contracted solar photovoltaic power purchase agreement for the fifth-phase Dubai solar park came in under two cents ($0.02) per kilowatt-hour (kWh). Barakah’s projected levelized cost of energy (lifetime costs divided by energy production) back in 2012 was a little over seven cents ($0.07) per kWh.

Meanwhile, Lazard’s 2019 global estimate for the average global levelized cost of nuclear energy came in at $0.118- $0.192 per kWh.

“Renewable costs have plummeted to such an extent that the market just says ‘no’ to nuclear,” said Dorfman. “The only way you can build nuclear these days is with massive, massive state subsidies.”

Not surprisingly, free markets have started to give a thumbs-down to nuclear energy. The number of nuclear power units under construction around the world fell from 68 at the end of 2013 to 46 by mid-2019.

Renewable costs have plummeted to such an extent that the market just says ‘no’ to nuclear.PAUL DORFMAN, FOUNDER AND CHAIR OF THE NUCLEAR CONSULTING GROUP

One reason construction is still moving forward with many of these, says Schneider, is nuclear power’s momentum.

“This technology is a lock-in technology,” he said. “Once you do the first step, it’s very difficult to walk back the decision-making processes.”

When the UAE established its programme in 2009, nuclear was more cost effective for generating electricity than solar and wind. But Barakah did not break ground until 2012 – after Fukushima had led many countries to either scrap or postpone nuclear projects, and by which time solar costs were closing in on nuclear and wind had become an even cheaper option.

“There was definitely a lost opportunity, you know, [for the UAE] to get out of this project,” said Schneider.

Proliferation concerns

Whenever the words “nuclear” and “Middle East” are uttered in the same sentence, a discussion about proliferation risks is almost surely bound to follow because nuclear technology is dual-use.

“The tense geopolitical environment in the Gulf makes nuclear a more controversial issue in this region than elsewhere, as all new nuclear power provides the capability to develop and make nuclear weapons,” Dorfman notes.

This has long been a concern in the Middle East – a region wracked by armed conflict, civil unrest and superpower agendas.

A cold war between Saudi Arabia and Iran has opened multiple faultlines. The air, land and sea blockade of Qatar by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain and Egypt just entered its fourth year. The civil wars in Syria and Libya are also regional and international proxy wars. Anti-government demonstrations erupted last year in Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, Palestine and Tunisia. There has been no progress in resolving the more than half-century-old Palestinian-Israeli conflict. And the COVID-19 pandemic is causing painful economic disruptions that are already fuelling more discontent.

All new nuclear power provides the capability to develop and make nuclear weapons.PAUL DORFMAN, FOUNDER AND CHAIR OF THE NUCLEAR CONSULTING GROUP

For years, the lightning rod for Middle East nuclear proliferation discourse has been Iran and the slowly unravelling deal with world powers to keep Tehran’s nuclear programme in check.

The Middle East is not a region where trust on matters nuclear is easily extended by the international community. And for good reason. Israel has never admitted to possessing nuclear weapons even though it is widely believed to have them. Iraq had a covert nuclear weapons programme that was gutted after the 1991 Gulf War. Libya admitted in 2003 that it had a clandestine nuclear programme that was subsequently dismantled. Algeria admitted in the early 1990s that it had constructed a nuclear research reactor with China’s help. And though Iran insists its nuclear programme has never been military in nature, it did admit in 2002 that it had built nuclear facilities that were not declared to the IAEA.

Understandably, the UAE has tried to distance itself from bad behaviour – real or perceived – of its regional cohorts.

Most recently, the UAE’s ambassador to the US, Yousef Al Otaiba, wrote an op-ed published in the Wall Street Journal reminding the world that the UAE had opted to “forgo domestic enrichment and reprocessing of nuclear material”, and has agreed to let the IAEA inspect its nuclear facilities on short notice.

“New and better rules have delivered a new huge source of clean power and reduced the risk of nuclear proliferation,” Otaiba wrote.

But concerns still linger.

“Since new nuclear makes little apparent sense in the Gulf, which has some of the best solar energy resources in the world, the nature of the interest in nuclear may lie hidden in plain sight,” Dorfman noted in a report he authored on Barakah.

Sokolski also has questions about Middle East nuclear energy ambitions. “If they want electricity, this is a very poor way to do it,” he said, noting the abundance of alternative energy sources the UAE could harness including natural gas, sun and wind. “Building a nuclear power plant would be like number 58 on your top five things to do, and that they’ve chosen to focus on this [nuclear] is suspect.”

And though being suspect is not the same as engaging in prohibited activities, the possibilities for something to go horribly wrong in connection with Barakah are too profuse to ignore, say experts.

Because when nuclear risks become nuclear reality, it may simply be too late.

“The point about these risks – these so-called low-probability but high-impact risks – is that they really do happen,” said Dorfman, “and when they happen, you really can write off a lot of people’s lives.”

SOURCE: AL JAZEERA NEWS