Why does missile defense still enjoy bipartisan support in Congress?

Posted: 25th September 2020

By Subrata Ghoshroy, September 24, 2020

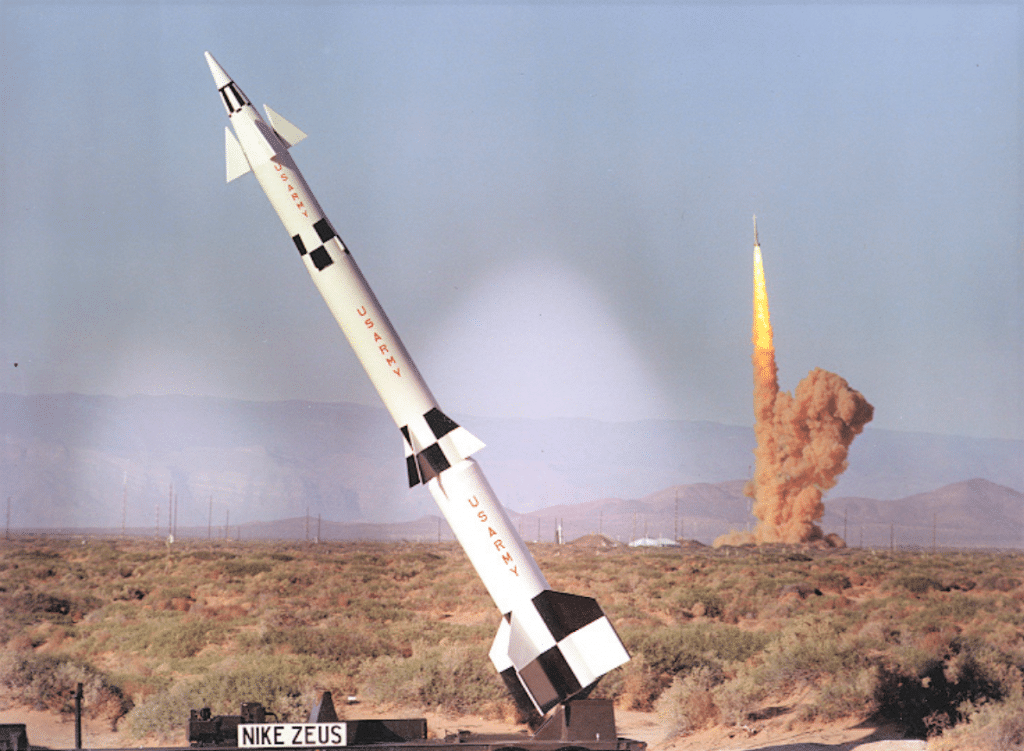

The Nike Zeus antiballistic missile system, developed in the 1950s and 1960s, was designed to defend against a Soviet nuclear attack against the US mainland. It was never deployed. Photo credit: public domain.

The program to develop a missile defense system to protect the United States mainland has existed in one form or another for nearly six decades. Though it was controversial from the beginning and faced nearly unsurmountable technical challenges, it has enjoyed bipartisan support and continued funding in Congress for more than 20 years.

In July, both the House of Representatives and the Senate passed their own versions of a defense authorization bill for 2021. By a wide majority, both chambers authorized more than $740 billion for defense spending next year. Tucked away in the Senate bill was $20.3 billion for missile defense, and that funding could make it into the final version that lands on the president’s desk. While $20.3 billion may not seem significant in a $740 billion budget, it is nevertheless a startling figure. What’s more, US taxpayers have invested nearly $200 billion on missile defense in the past two decades and another $100 billion in the decade before, with little to show for it. Even under artificially easy tests conditions, the most modern missile defense system meant to protect the United States mainland has failed more times than it has succeeded often in highly scripted tests.

When Congress gets serious about cutting waste from the federal budget so that social needs like healthcare and efforts to combat climate change can be funded, missile defense will be a low-hanging fruit.

To understand how and why a program that is unproven, arguably unnecessary, and even counterproductive has survived for so long, we have to go back to the beginning.

A history of the US missile defense program. Intercontinental ballistic missiles burst into the Cold War foray following the Soviet launch in 1957 of the first ever earth-orbiting satellite named Sputnik. During the 1960 presidential election campaign, John F. Kennedy took a tough line on the Soviet Union and blamed outgoing President Eisenhower for the so-called “missile gap”—a perception among US officials that the United States trailed the Soviet Union in ballistic missile technology. After taking office, President Kennedy dramatically increased funding for missile and space programs. Antiballistic missile systems, designed to shoot down incoming missiles, followed.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the United States developed several antiballistic missile schemes, with names like Nike Zeus, Nike-X, Sentinel, and Safeguard. None of them proved feasible for defending against an all-out attack, much less against one that might involve incoming missiles tipped with not just one warhead each, but multiple.

The systems were also found to be destabilizing, since even the semblance of a US defense, however ineffective, pushed the Soviets to improve their offense, resulting in an arms race. In 1972, both superpowers woke up to the madness and agreed on the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, which all but banned such systems. The treaty would stay in force for four decades and paved the way toward more nuclear arms control.

However, a section of the US military and its supporters always bristled at the limits on the missile defense program. After Ronald Reagan became president in 1980, he ratcheted up the rhetoric against the Soviet Union, calling it the “Evil Empire,” and proposed to develop a missile shield over the entirety of US territory.

The research and development program he proposed was called the Strategic Defense Initiative. It called for the development of a wide array of sensors and weapons, including high-powered lasers, to be based on land, sea, and in space. Most of the proposal was a fantasy, however, as it was decades away from technical feasibility—which is why detractors began to derisively call it “Star Wars.”

While the United States continued to pledge its allegiance to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, it started pushing the Soviet Union, and later Russia, to amend the treaty to accommodate Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative program. The Soviets, however, repeatedly opposed such moves and argued that the treaty must be preserved to maintain global strategic stability.

Reagan tried to sell his initiative as a program that would achieve nuclear disarmament because it would render nuclear weapons useless. Moreover, he said that he would share the technology with the Soviet Union and other countries. But, when Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev proposed eliminating nuclear weapons altogether and also banning missile defense systems at a summit in Reykjavik, Iceland, in 1986, Reagan rejected it— though he notably did not withdraw from the anti-ballistic missile treaty during his tenure.

After Reagan, President George H. W. Bush scaled the missile defense program back drastically after the Cold War ended in 1991, aware of the fact that virtually none of the systems worked.

Yet, the missile defense lobby refused to give up. The 1991 Persian Gulf War was a turning point. Until then, missile defense was primarily about strategic defense against nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles. However, the Gulf War saw the introduction of shorter-range conventional missiles, such as the Scud missiles deployed by the Iraqi military. Although most Iraqi missile attacks were harmless because the missiles were so inaccurate, one strike proved to be devastating. It destroyed a US troop barracks in Saudi Arabia, reportedly killing 27 US military personnel and injuring nearly 100 others.

Although early reports suggested that the US Patriot anti-missile system had actually made the situation worse by shooting down a missile—and scattering deadly debris—that would have otherwise missed its target, the tragic incident gave new ammunition to the missile defense lobby. It began pushing for the development of theater missile defenses in addition to the strategic missile defenses envisioned by Reagan’s program. In the 1992 presidential election campaign, Bill Clinton campaigned against a space-based missile defense system but supported the development of a treaty-compliant theater missile defense system.

After the Republican takeover of both chambers of Congress in 1994, however, lawmakers sought to press ahead on strategic missile defense. The Republican leader Newt Gingrich, who led his party to victory, had made missile defense a central part of the “Contract with America.” Despite his initial opposition, President Clinton, facing a hostile Congress and engulfed in a scandal, cut a deal with Republicans. In July 1999, he signed the Missile Defense Act, which made it the policy of the United States to deploy a national missile defense system “as soon as is technologically possible.” The Democrats were able to wring out the small concession about technological feasibility, but the overall result was that the floodgates for the funding of missile defense burst wide open. Henceforth, missile defense virtually disappeared from the public view.

When George W. Bush was elected President in 2000, his administration moved aggressively to both increase funding and also expand the scope of the missile defense program. In 2002, the administration revamped the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization into the Missile Defense Agency, withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty, and decided to field a missile defense system as quickly as possible. The administration also used two procedural sleights of hand to give the Pentagon a free hand to continue spending money on missile defense with minimum oversight and accountability.

First, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld delegated to the director of the Missile Defense Agency the authority to dole out contracts under a special category called “other transactions.” Contracts in this category fall outside of the Federal Acquisition Regulations, meaning they are exempt from many of the typical laws and regulations that protect taxpayer interests. The mechanism was originally intended as a way to bring in nontraditional contractors and to expedite small programs to undertake rapid technology development to counter imminent threats. But it was highly unusual to delegate this authority to a major defense acquisition program whose expenditures already exceeded billions of dollars. When missile defense was placed under this category, Congress had less insight into the program and its spending.

Second, the Bush administration decided to keep the program under the “research and development” category, even though it had already been deploying missile defense systems both in the United States and abroad. Normally, defense acquisition programs go through several stages of “research, development, test, and evaluation” before entering the “procurement” phase. The milestone to enter procurement is critical, because the system has to pass rigorous testing to ensure it is deployable in the battlefield. Although the program has been in a de facto “procurement” phase since the early days of the Bush administration, when it was deployed to multiple sites in the United States and abroad, it has remained filed under the research and development category. It has thus far avoided the stringent independent testing that is required for a system to enter “procurement.”

All told, the United States has spent more than $300 billion for missile defense research and design over a period of about three decades. It spent about $30 billion—approximately $55 billion in current dollars—on the Strategic Defense Initiative between 1984 and 1993, when the program was canceled, according to a report published by the US Government Accountability Office. After that, during the Clinton years, missile defense managed to garner approximately $5 billion each year through Congressional earmark funding, for a total of about $35 billion in then-year dollars, or about $55 billion in current dollars. And Since Rumsfeld’s changes in 2002, the program has received about $10 billion each year in constant 2018 dollars with bipartisan support, for a total of about $190 billion.

Ending the defense contractor honey pot. Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative was a turning point because it provided substantial funding for missile defense research and design. It was as though the defense contractors who were engaged in this research had suddenly found gold in a Wild West landscape. The initiative became an uncontrollable and unaccountable program with lax oversight, resulting in wasted taxpayer money and virtually no advancement in missile defense technologies.

Over the years, the contractors have made generous contributions to the campaign coffers of lawmakers of both parties to keep the funds flowing. It has especially targeted members of the House and the Senate Armed Services Committees, which authorize funding for defense programs, as well as and members of the Appropriation Committees, which control the purse strings. According to the Center for Responsive Politics, over the last 10 years the defense industry as a whole spent more than $20 million each election cycle in contributions to individual candidates and political action committees, and hundreds of millions of dollars per year on lobbying. In 2018, both Republican Mac Thornberry, the ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee, and Democrat Adam Smith, the committee chair, took hundreds of thousands of dollars in campaign contributions from the defense sector.

Today, support in Congress for missile defense is so strong that only a wave of intense public pressure could alter the situation.

But the time is ripe for just such a wave. Because of budgetary pressures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, there will simply be not enough money, if defense remains a sacred cow, to fund urgent social needs without creating huge deficits. There is a growing chorus of demand to reduce funding for the police and transfer the funds to house the homeless, for example. There must be an equally strong public outcry against a $740 billion carte blanche to the Pentagon, which is roughly half of the $1.485 trillion discretionary budget that pays for everything else.

The place to start is the missile defense programs, which have received hundreds of billions of dollars of funding over the years, with little to show for it. According to Laura Grego, a missile defense expert at Union of Concerned Scientists, the system currently deployed to protect the continental United States from an incoming ballistic missile attack has failed nine out of its 18 tests over the last 20 years. More worrying is that it has not improved over time, failing sixty percent of tests since being deployed in Alaska and California. And even if it had a better testing record, experts have long recognized that any missile defense system could be easily defeated by decoys and other countermeasures.

Under the present political balance of power, the Senate is unlikely to take any action that might put the program under a spotlight. However, the relevant House committees should hold robust hearings as soon as possible, with truly independent witnesses who can testify on the program’s ineffectiveness. In particular, the House Committee on Oversight and Reform, which has subpoena powers, should determine if the use of the “other transaction” contracting mechanism for such a large program is appropriate. It should also determine why the program has remained in the “research and development” category for two decades while deploying systems on the US mainland and abroad. In this time of great economic hardship, Congress cannot afford to waste taxpayer money. It is time to end the bipartisan consensus on missile defense.