Rethinking nuclear security for a world free of nuclear weapons

Posted: 2nd November 2020

From the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

By Kennette Benedict | November 2, 2020

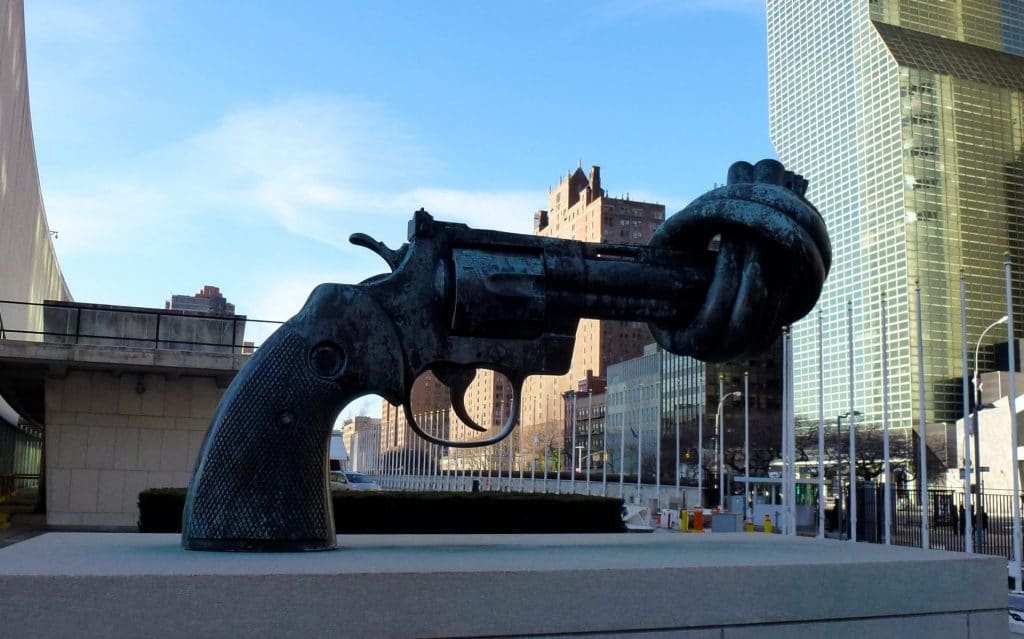

Non-Violence, a sculpture outside the UN building in New York. Credit: creative commons.

Non-Violence, a sculpture outside the UN building in New York. Credit: creative commons.

Recent news reporting has suggested that President Donald Trump is racing to conclude a nuclear arms agreement with Russian President Vladimir Putin that both sides can sign before the US election. The details of the potential agreement are few but, at this writing, it would seem to include a “freeze” on warheads and a one-year extension of New START, the treaty that caps US and Russian deployed nuclear arsenals and that expires early next year.

Since the beginning of the nuclear age in 1945, this kind of negotiation to reduce or limit arsenals was one of the primary ways by which the nuclear powers sought to lessen the risks of a nuclear catastrophe. A parallel effort has sought to deny nuclear materials and technology to countries that do not already have them. Together, these efforts have been quite successful—today only nine countries possess nuclear weapons and nuclear weapons stockpiles are dramatically lower than they were in the 1980s. Yet, although both strategies rightly accept the danger of nuclear weapons, neither one fundamentally questions the assumption that nuclear deterrence is a policy that will keep the nuclear powers and the world safe.

As the pandemic subsides over the next several years, the United States will have the opportunity—perhaps the obligation—to rethink this arrangement. Two new approaches in particular may help place nuclear deterrence under the spotlight and reduce the importance of nuclear weapons in US national security. The first is based on the idea of human security and flows from recognizing the effects of detonating nuclear weapons on populations, whether by accident, miscalculation, or war-fighting. The second highlights the democratic deficit in decision making about nuclear weapons in all nuclear weapons states, but most keenly in the United States.

These two approaches—emphasizing human security and democracy—could help shift the frame of reference and provide the basis for a world free of nuclear weapons.

Denying and negotiating. The drive to deny fissile material and technology to governments seeking nuclear weapons has a long history. For example, the 1963 Limited Test Ban Treaty between the United States and the Soviet Union banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere that would have promoted even more rapid development of nuclear bombs. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (signed in 1968) allowed the existing nuclear weapons states to keep their arsenals but denied the right of non-nuclear weapons states from acquiring their own nuclear weapons. Most recently, the US-sponsored Nuclear Security Summits of 2010–2016 pressed countries to get rid of their nuclear bomb-making material by sending it back to one of the five nuclear weapon states. This effort prevented terrorist groups from acquiring bombs and limited the number of new countries possessing nuclear weapons by denying them the enriched uranium and plutonium for making bombs.

These initiatives have been favored by scientists and engineers who propose them as technical solutions to nuclear weapons dangers, and they have succeeded in stemming the tide of new nuclear weapons states. Only India, Pakistan, and North Korea have tested nuclear weapons since the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty came into force, and while Israel remains an ambiguous nuclear power, no other states have successfully developed these weapons of mass destruction. Some 23 to 40 countries had the know-how and the motivation to embark on nuclear weapons programs but refrained from doing so as signatories to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

A second effort has involved establishing dialogue among experts and scientists, and then government officials, from rival nuclear weapons states to build trust, agree on how to verify agreements, and limit nuclear weapons arsenals. Talks began soon after the start of the US–Soviet arms race in the 1950s and have yielded substantial results over the years, including the Limited Test Ban Treaty, START and New START between the United States and Russia, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (not yet in force) that outlaws all nuclear weapons testing worldwide, and the Cooperative Threat Reduction program of 1994, which jointly deactivated some 13,300 warheads and eliminated 1,473 intercontinental missiles from the US and Russian nuclear arsenals.

Human security. These two methods—denying and negotiating—have yielded impressive results: a 60 percent reduction in US and Russian nuclear weapons since 1987, increased communications between military establishments, and only a handful of countries that have gone nuclear. Despite the successes, however, nuclear weapons still remain potent symbols of military and state power and are used to threaten adversaries and assure allies as if they can provide reliable security. And neither of these two methods questions the utility of nuclear weapons or their legitimacy in regulating international security affairs.

A new approach to reducing the dangers from nuclear weapons, known as human security, recognizes the inherent value of human beings and the requirements for their protection. In nuclear security, that means focusing on the humanitarian effects of nuclear weapons and challenging prevailing policies based on nuclear deterrence.

In brief, because just one nuclear bomb has such catastrophic consequences, there are no effective means of defending against them. The lack of defenses is thought to serve as the basis of restraint; leaders are not willing to sacrifice their own citizens in nuclear war, so none will launch nuclear weapons first for fear of nuclear retaliation. In effect, such deterrence policies—the daily threat to use nuclear weapons against any adversary—rely on a mutual suicide pact between and among government leaders. Such mass killing would violate international law, however, and contradicts the value of human life, elevated in the idea of human security.

The idea of human security emerged in the mid-1990s as the Cold War was ending and the international order based on US–Soviet competition was in disarray. As genocide in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda challenged the international community to protect peoples in those countries and elsewhere, the responsibility of government leaders and the international community to provide for the safety and well-being of citizens came into sharper view. Human security proposes a renewed focus on the social contract between state and citizen, where the state has a responsibility to protect its own people from forces within the country as well as those from without.

Based on this concept of human security, international civic organizations, including the International Committee of the Red Cross, the International Physicians to Prevent Nuclear War, and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), have worked successfully with the United Nations and member states to pass a treaty in 2017 that prohibits the production and use of nuclear weapons. ICAN and its leader Beatrice Fihn received the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for their work to draft and publicize the treaty. And since it recently reached the 50-ratification threshold needed to enter force, it will become international law in January 2021. The goal is to stigmatize nuclear weapons, and to prohibit their manufacture and use. Just as chemical and biological weapons, as well as land mines, are viewed as illegitimate weapons of war and are banned under international law, nuclear weapons will also be banned.

Democracy and the Bomb. Finally, a clear-eyed examination of nuclear weapons policy and practice reveals the undemocratic nature of these weapons of mass destruction. In the United States, the president—even one who is a heavy drinker or is taking mood-altering drugs—has the unilateral, unchecked authority to launch nuclear weapons. That fact, combined with war plans and launch postures that send hundreds of nuclear missiles to targets half-way around the world within 30 minutes of a command, place nuclear weapons policy outside of any democratic control—control that the founders called for by lodging the power to declare war in the hands of Congress.

Over the past four years, Congressional members have begun to question the president’s unusual power to start nuclear war and have introduced legislation that prohibits the president from launching a nuclear attack without a declaration of war by Congress (Restricting First Use of Nuclear Weapons Act of 2019—HR. 669/S.200), as well as other proposed laws to reduce the president’s sole authority to launch nuclear weapons first. These and other proposals deserve much broader discussion as the country begins to rebuild its democratic practices.

The COVID-19 pandemic has killed over 220,000 people in the United States alone. As horrible as that tally is, it pales in comparison to the numbers who would be killed in a nuclear attack. US government mortality estimates of a nuclear exchange with Russia are in the range of 600 million dead. These deaths are completely preventable if political leaders take seriously their duty to protect their own citizens—the essence of human security—and move to a world free of nuclear weapons. Our democracy requires no less.