Four ways the killing of Iran’s nuclear scientist will undercut US national security

Posted: 3rd December 2020

From the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

By John Krzyzaniak | December 1, 2020

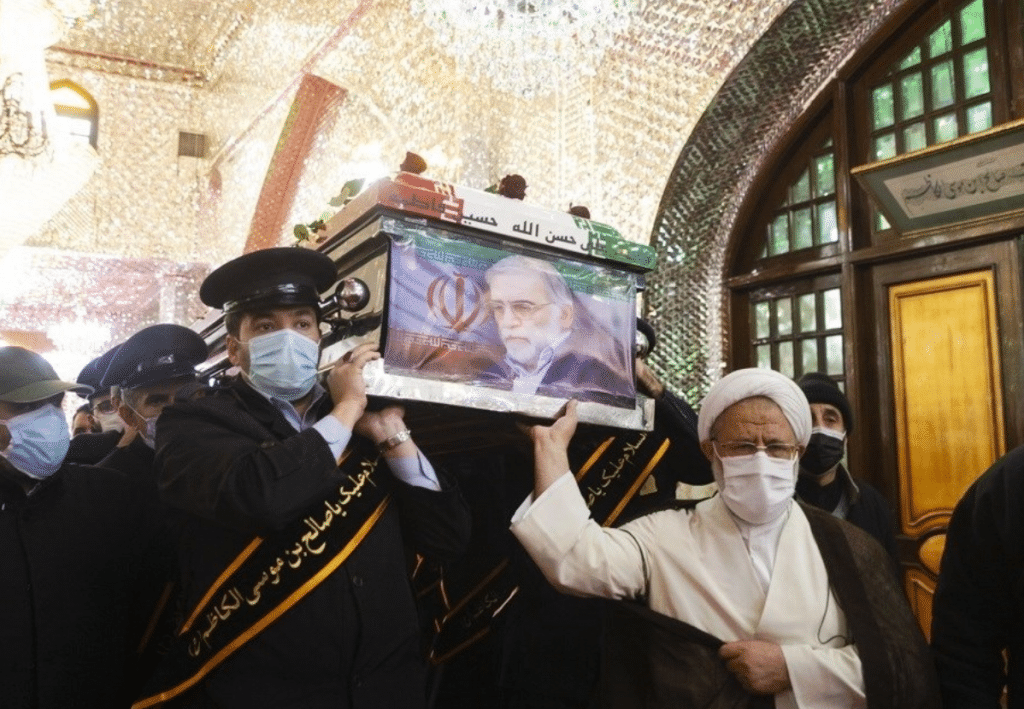

The funeral procession for Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a top Iranian nuclear scientist. Photo credit: Saeed Sajjadi for Fars News.

Last Friday, Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a leading Iranian nuclear scientist, was shot in broad daylight in Absard, 45 miles east of Tehran, on his way to visit his in-laws. It took only hours for Iranian officials to begin pointing the finger at Israel. That same day, Mohammad Javid Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister, wrote on Twitterthat the attack had “serious indications of [an] Israeli role.”

It is impossible to know for certain, but top US officials may have been aware about the operation in advance and might have even given their tacit or explicit approval. US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had just met with Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu in Saudi Arabia a week earlier. And, just a few weeks before that November meeting, President Donald Trump reportedly sought options to strike at Iran’s nuclear program, though his senior advisers apparently dissuaded him.

At first, the Fakhrizadeh assassination may seem to bring security benefits to the United States and its partners. As Ariane Tabatabai, the Middle East fellow at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, wrote in Foreign Policy, the killing exposes the weakness of Iran’s internal security and puts Tehran in a bind. Iran’s leadership will feel compelled to retaliate to avoid looking weak and to try and deter future attacks. However, if it does retaliate, it risks sparking a wider conflict, which Iran does not seek.

Despite this initial realpolitik appeal, however, over the longer term the killing will likely damage US interests in four ways.

First, the killing sends the message that the illegal assassination of scientists and public officials is acceptable behavior for all countries to engage in. This is a point that US Sen. Chris Murphy made on Twitter: “Every time America or an ally assassinates a foreign leader outside a declaration of war, we normalize the tactic as a tool of statecraft.” US officials across the world are now at increased risk of becoming targets themselves.

Second, killing Fakhrizadeh will not set back Iran’s nuclear program and may eventually strengthen it. Bruce Riedel, who worked at the CIA for 29 years and is now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told the New Yorker’s Robin Wright, “No individual is crucial in a nuclear program like this anymore… That’s why describing [the assassination] as a devastating blow is nonsense.”

The same was true a decade ago, when a series of Iranian nuclear scientists were killed under mysterious circumstances. In 2012, William Tobey, a nuclear expert who served on the US National Security Council under three presidents, explained why, after four scientists had been killed, the setbacks were likely to be short-lived at best. “Nuclear weapons programs are large, complex undertakings, involving hundreds of key people. Killing a few workers, even if they are talented and working on important projects, will not halt the undertaking,” he wrote.

In some circumstances, Tobey explained, such assassinations may discourage other scientists from wanting to work on the nuclear program, and a country undertaking an assassination may see that as a benefit. However, Iranian scientists have been well aware of the risks to their personal safety for years, precisely because of the string of murders that took place from 2010 to 2012. Fakhrizadeh’s death will not change that calculus.

In the short term, a high-profile attack may marginally slow down Iran’s nuclear program, as officials devote more time and effort to beefing up measures to ensure operational security. But in the longer term, that could translate to less transparency and greater secrecy, making it harder for the West to glean insights into the nuclear program that could prove beneficial in future diplomatic talks or military strikes.

Third, Iran could use the attack as a pretext to reduce its cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), the global nuclear watchdog that has unprecedented access to Iran’s nuclear sites.

In fact, every time there is some act of sabotage or assassination related to Iran’s nuclear program, Iranian officials find a way to connect it to the agency’s inspectors in some way. In 2011, at the IAEA’s general conference, Fereydoon Abbasi, then head of Iran’s Atomic Energy Organization and himself the target of a prior assassination attempt, suggested that the agency had “prepared the ground” for the string of attacks against the nuclear scientists by sharing their names and addresses with member countries.

More recently, following the explosion at Iran’s Natanz enrichment facility, an ultra-conservative member of Iran’s parliament claimed that the agency’s inspectors were acting as spies for the West and that information they had collected contributed to the sabotage operation.

This time around, following the death of Fakhrizadeh, Iran’s parliament moved quickly to pass a measure to force the government to suspend Iran’s implementation of the Additional Protocol, an agreement that gives IAEA inspectors increased visibility into a country’s nuclear sites. (Following the 2015 nuclear agreement between Iran and world powers, Iran began implementing the Additional Protocol on a voluntarily basis and agreed to formally ratify it in 2023.)

That is not to say that Iran will follow through on suspending implementation of the Additional Protocol, let alone withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. These would be radical steps and are highly unlikely. The recent act of parliament contained several ifs, ands, and buts, and the Rouhani government acknowledges that the legislature has no real authority over the nuclear file in any event.

But there are other, less radical measures Iran could take to decrease cooperation. One way would be to curb the International Atomic Energy Agency’s access to the scientists who work on the nuclear program. As Reuters reported in 2014, the agency had long sought to meet with Fakhrizadeh himself “as part of a protracted investigation into whether Iran carried out illicit nuclear weapons research.” But Iranian officials refused to allow it, citing worries that his talking with agency inspectors would put him at risk and could lead to his assassination.

This kind of access is important in enabling the International Atomic Energy Agency to build a full assessment of a country’s nuclear activities. “Safeguards verification is analogous to creating a mosaic: Without access to individuals, IAEA inspectors would not have half the tiles they need for a complete and accurate picture,” Tobey, the former US National Security Council official, wrotein 2012.

Fourth, the assassination will make US–Iran diplomacy more difficult. Of course, for those who are opposed to the 2015 nuclear agreement and are worried that President-elect Joe Biden will return to it, scuttling diplomacy before it begins was the whole point.

Some may be inclined to believe that the killing could actually facilitate diplomacy. In a column for the Washington Post, Max Boot, a historian and well-known foreign policy analyst, made that exact argument. In the same way that the assassinations of Iranian scientists from 2010 to 2012 helped put pressure on the Iranians and forced them to the negotiating table, he wrote, perhaps this assassination will also make a deal more likely.

That flies in the face of common sense and is wrong on two counts. First, it is at odds with the historical record. It is something of a myth that American pressure brought the Iranians to the table during the Obama administration; if anything, Iranian pressure brought the Americans to the table.

Beyond that, the context today is quite different. The United States does not need more pressure to force the Iranians back into the nuclear agreement—Iran wants back in. Nor was it the party that withdrew in the first place. Moreover, the Trump administration has spent four years testing the hypothesis that adding ever more pressure could force Iranian capitulation, and it hasn’t worked.

For anyone sensible enough to recognize that diplomacy is the only way to ensure Iran’s nuclear program remains peaceful over the long term, the murdering of a scientist creates costs and brings few if any benefits.

Some Iranian officials have already bristled at the idea that Iran should accept a clean return to the nuclear agreement when Biden enters office. They believe, for example, that the United States should not only lift sanctions, but should pay Iran “compensation” for the damage caused by those sanctions while Iran upheld its end of the bargain. Killing a scientist only adds to the list of grievances, reduces trust, and complicates the return to the deal that Rouhani’s government is seeking.

All of the negative repercussions of the Fakhrizadeh assassination will occur, even if Iran chooses not to retaliate. If it does strike back though, the consequences could be that much more damaging to US interests.