Local despair over Fukushima’s radioactive mushrooms

Posted: 11th December 2020

“I had never imagined we would be affected by a nuclear accident,” says Tsutomu Jinno, a 71-year old who used to head a matsutake mushroom harvesting association in the town of Tanagura in Fukushima Prefecture.

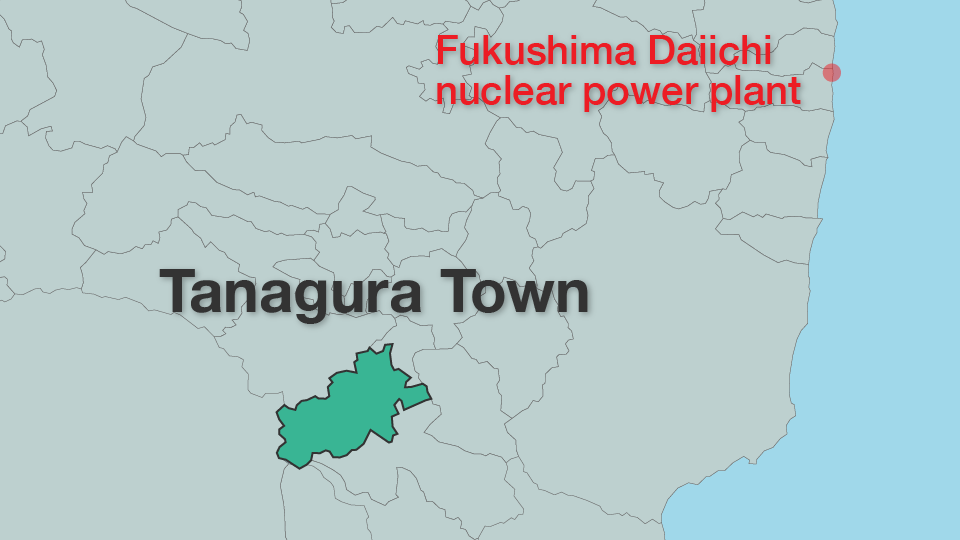

Tanagura is more than 80 kilometers from the nuclear plant, but in the summer of 2011, high doses of radioactive substances were detected in the area’s wild mushrooms.

These days, radioactivity barely registers in the rice or vegetables grown there, but the wild mushrooms are a different story. Japan’s standard for radioactive cesium in general food is 100 becquerels per kilogram. The levels in Tanagura’s matsutake mushrooms are still three times that.

Tanagura’s matsutake had a reputation for their exquisite taste and aroma. Tourists used to flock to the region each autumn to pick them, and the delicacy was an important source of income. Jinno holds on to a hope that those days will return.

He still forages, but now it’s to prevent others from collecting them illegally. Within about three hours, he has filled a basket, but there’s nothing he can do with them. “Honestly, it is painful to throw them away,” Jinno laments.

Reasons for high radioactive readings

Almost all of Fukushima prefecture is covered by a ban on the shipment of wild mushrooms.

Hiroi Masaru, a former professor at Koriyama Women’s University, says mushrooms like matsutake grow on a layer about five centimeters below the ground and that layer, formed by decaying foliage and argillaceous soil, is prone to absorb the cesium contained in leaves. In areas that see heavy winter snowfall, it takes a long time for dead leaves to decompose. This is part of the reason cesium levels in some mushrooms began to increase three to five years after the nuclear accident.

Hiroi says government standards must be adhered to, but he wonders if the rules are too restrictive: “Strict standards are necessary for foods we eat on a daily basis, such as rice, but we only consume mountain vegetables or wild mushrooms several times a year. The current radioactive levels would cause almost no harm.”

Moreover, Japan has tougher guidelines than the global rules. The Codex Alimentarius, an organization that sets international food standards, limits radioactive cesium in food at 1,000 becquerels per kilogram. The Japanese standard of 100 becquerels is ten times stricter.

Tsutomu Jinno, a 71-year-old who used to head a matsutake mushroom harvesting association in Tanagura, Fukushima Prefecture.

Hurdles for lifting shipment bans

Because of the wide variety of wild mushrooms, it is often difficult for ordinary people to tell one species from another. If one type is found to have too much of a radioactive substance, shipments of all wild mushrooms from the municipality are halted.

And the process to get the ban lifted is long and complicated. Municipal authorities have to gather samples of a specific species from more than five locations and confirm that the radioactive substances are under the standard of 100 becquerels. The same test is conducted the following year to see if the levels have declined further. In the third year, samples are collected from 60 different locations in the municipal area – and if they all clear the 100 becquerels standard, restrictions can be lifted.

A health ministry official told NHK that there is not enough data for a review yet.

Disappearing food culture

For people in Tanagura, matsutake mushrooms were more than just a source of income. They had a role to play in keeping the community together. Jinno says it’s also regrettable that children are losing interest in seasonal foods.

“People used to gather seasonal wild vegetables in the mountains and cook them,” he recalls. “Since the nuclear accident, they have stopped doing that and our food culture is becoming lost. Children can’t become interested in foods that are not on their table, but it is virtually impossible to decontaminate the vast mountains. It’s been ten years since the accident. I have almost given up hope.”Correspondent